My dad was six feet tall, but he had hands and feet fit for someone five inches shorter. He was born in the Year of the Rabbit, a zodiac that exudes calmness and inherent aversion to the spotlight, and yet he became a tutor, which drew him more attention than most other jobs in the city. He could afford Porsches in his forties, but he grew up having to walk many miles to school.

He used to tell me stories about the 300 square-foot room all 14 members of his family lived in. How he’d squeeze into the corner of the bed to study for a test, while his older siblings were forced to work at 13 years old. How the whole family shared a small fish for dinner and he’d be given the eyeball because his mother loved him best. But there was never a hint of bitterness or self-pity in his voice as he recollected the summers he spent manufacturing key chains to earn a few cents. He’d just stare past me as he spoke, with an unintended smile on his face and his voice would drop to a whisper. But just as he started to touch upon the severely impoverished moments of his childhood, he’d end it with a punch line. “Then one time my sister got the fish eye instead so I tackled her until we broke the chair and this is how I got the scar on my nose.”

Some people find it incredible that someone who came from threadbare shoes could still retain a sense of humor. But my father would say that humor is what keeps one going in the direst of times. So as he became the first one of his family to receive a college degree and earn the highest salary, he couldn’t resign from his position as CEO of Cheeky Inc.

As we lay by the infinity pool under the Balinese sun, a waiter came and placed a little glass jar on the table that seemed to contain some kind of white fluid. Curious, I asked him what he ordered to which he replied, “Milk, for my alcohol.” I nodded, “oh” and returned to my magazine when my mother joined us after her spa. When I turned back to him, I saw him lathering the “milk” all over his body and my mom said, “Honey will you pass the sunscreen when you’re done?” Till now I don’t know how many other times he has deceived me with an impenetrable poker face, but these are the moments that I attach the word Father to, the one who conceals the truth from me to make room for my imagination.

My mother is a tiger by the Chinese zodiac, so she enjoyed taking the reigns that he so willingly relinquished. He would ask her what she wanted to order at the restaurant, then he’d order her second choice, so she’d be able to have a taste of both. He’d peel her pears before she woke up for breakfast or wait hours for her to get ready for a dinner at Prosecco with his only complaint as, “Why do you look so beautiful? Now I have to go change to match you.” When my mother was deeply dissatisfied by a service, they would lapse into their good cop bad cop game, with my mother wielding the baton. But occasionally she would hand him the stick:

“What the hell do you mean we can’t get a refund on our taxes? We don’t even live here!” he said exasperatedly, as I stood embarrassed by the racket we’re causing at the Taiwanese airport.

“He means, please give us our money back,” she said, as the staff member shook her head.

“I LOVE TAIWAN, YOU KNOW?? I COME HERE EVERY YEAR! I AM A VERY RICH MAN! I DON’T NEED YOUR MONEY! GIVE ME MY REFUND!” he yelled hysterically.

“Honey, don’t scare the poor lady”

“I LOVE TAIWAN! DO YOU LOVE TAIWAN? WE LOVE TAIWAN! GIVE ME MY MONEY NOW!”

And what do you know? We got our money back. And it’s probably because he succeeded in confusing the poor lady into submission. To those standing behind us in line, my dad would have come across as someone who has forgotten to take his pills, but he just simply didn’t care what they thought of him. He’d tell me, “live your life as someone who people fear and not someone who fears others.”

Indeed, fear has never been able to govern any of his actions. On one of our first ski trips to Japan, my mother, the escape artist who flourished on the steep slopes of Canada, was determined to teach my dad and me to ski. I was up first, so we left him near the chairlifts, and I skidded down the slope, slowly but surely, my legs spread in a V with my mother following closely behind. Suddenly, we catch a glimpse of my dad speeding straight down the hill, and just as I was about to be impressed by how fast he was going, we hear a brief yelp, and realized he was skiing uncontrollably, straight into the trees below. When we finally reached him, his skis were flung into the snow like javelins and his laugh echoed off the trees.

“What on earth were you thinking?” my mom demanded.

“I was bored waiting at the top!” was the only explanation we got.

Yet beneath his eagerness to fall lay an unwavering resolve to always cushion the drop for those he loved. It was almost a stubborn drive to be there for me or my mother, an impulse so urgent and necessary, that it felt as if something in him was broken and he was trying to fix it, to compensate.

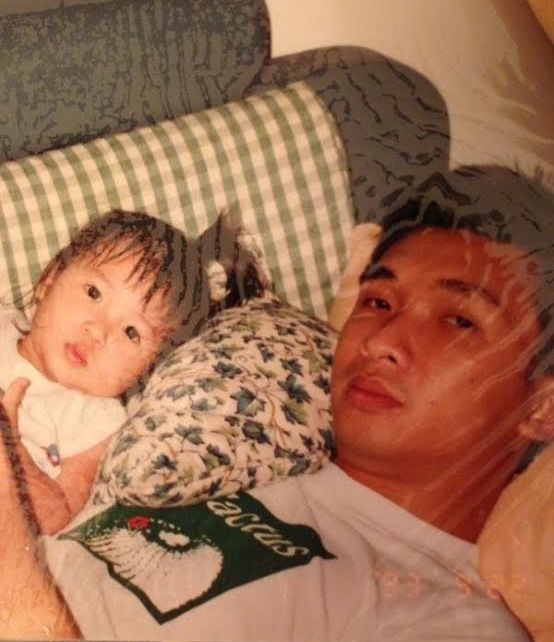

My mother, the face of their company and an outspoken public figure, was always the less available parent. While she would inflict violence on anyone who disturbed her precious few hours of sleep, my dad woke up to the sound of me creeping into their bed after dreaming about someone chasing me. Some nights when the birds’ chirping jolted him out of his worry-plagued stupor, he’d make hot chocolate for me as I got ready to go to school. All that was said was communicated through the silences of these mornings and troubling dreams of the night where he’d let me know that he loved me and would always be there for me. He wanted to be sure I knew that.

I don’t know when it started, but every Sunday while my mother and I were sleeping, he’d take a rag and stool from the kitchen and sit on the balcony near our seven-foot plant. Then he’d gently wipe the surface of every heart-shaped leaf, his knees cracking as he stooped for the lower branches. He’d lock the glass door so nothing could be heard from the living room. I could not understand why he seemed so pained, why his thoughts withdrew into himself so that the corners of his smile seemed pinched, stunted. He’d forget his keys, wallet or phone every other day; I’d have to ask him the same question over again because instead of looking at me he was looking at himself the first time. But one day, he spoke to me.

Coming home from work, I followed him into their bedroom to tell him about the school concert. He stared into the basin intently as he washed his hands and said, “You know, every time I wash my hands, I think about the days I’d come home from visiting your grandma at the hospital.” When my grandmother was ill with a kidney disease that slowly eroded her time, my dad was her only child that watched over her. But when she passed away, he felt that he could have done better, provided her with better doctors, put her in a more expensive hospital, anything. The success he had accomplished seemed futile, the money he earned seemed excessive if she couldn’t be here to share it. And so he punished himself, shut off his ability to feel, and only smiled to keep other people’s worlds turning.

The duality of his personality could come across as bipolar or neurotic, but it is only now that I realize, he was always responsible for everyone else and reckless when I came to himself. It was how he could pull any antic to make a somber room laugh, but couldn’t bring himself to smile. How he could protect me or my mother at his own expense, but drive with his laptop open next to him. How he would ensure I wore my seatbelt but go racing his car that night that took his life.

Didn’t he realize that his audacity could inflict consequences on the very people he swore to protect? How is he supposed to protect us now? How could he be so stupid?

As these thoughts pounded through my head and hot, angry tears streamed down my face, I stared at the white roses the congregation placed on his coffin. He was about to be cremated and everyone was circling around to say goodbye as the priest was mumbling a prayer. Suddenly, the coffin began descending into the platform where the furnace would be. The priest looked startled and realized he had accidently pushed the lever, and there was no turning back. While everyone exchanged horrified expressions, fearing this would upset my mother, she and I looked at the coffin that was slowly disappearing into the ground, glanced at each other, and burst into laughter.

We laughed because we could see his face, and the smirk that always danced around his lips when he was about to pull a prank. We could see his brows raised in impatient defiance at the grueling pace of the procession and his brimming desire to purge the room of tears. As the coffin was cast into the fire, we could hear his voice echoing above the priest’s, chuckling, “I just got bored waiting at the top!”

P.S. I chose the song "Alone Again (Naturally)" not for its lyrics but simply for its melody. It was the song I listened to as I wrote this piece and I felt that its melancholic yet happy-go-lucky tune also perfectly sums up my father's disposition. Thanks for reading!